Callbacks, Promises, Async/Await

This is originally part of our Advanced JavaScript course. However, it’s applicable to us here as well.

One of my favorite sites is BerkshireHathaway.com - it’s simple, effective, and has been doing its job well since it launched in 1997. Even more remarkable, over the last 20 years, there’s a good chance this site has never had a bug. Why? Because it’s all static. It’s been pretty much the same since it launched over 20 years ago. Turns out sites are pretty simple to build if you have all of your data up front. Unfortunately, most sites now days don’t. To compensate for this, we’ve invented “patterns” for handling fetching external data for our apps. Like most things, these patterns each have tradeoffs that have changed over time. In this post, we’ll break down the pros and cons of three of the most common patterns, Callbacks , Promises , and Async/Await and talk about their significance and progression from a historical context.

Let’s start with the OG of these data fetching patterns, Callbacks.

Callbacks

I’m going to assume you know exactly 0 about callbacks. If I’m assuming wrong, just scroll down a bit.

When I was first learning to program, it helped me to think about functions as machines. These machines can do anything you want them to. They can even accept input and return a value. Each machine has a button on it that you can press when you want the machine to run, ().

function add (x, y) {

return x + y

}

add(2,3) // 5 - Press the button, run the machine.

Whether I press the button, you press the button, or someone else presses the button doesn’t matter. Whenever the button is pressed, like it or not, the machine is going to run.

function add (x, y) {

return x + y

}

const me = add

const you = add

const someoneElse = add

me(2,3) // 5 - Press the button, run the machine.

you(2,3) // 5 - Press the button, run the machine.

someoneElse(2,3) // 5 - Press the button, run the machine.

In the code above we assign the add function to three different variables, me , you , and someoneElse . It’s important to note that the original add and each of the variables we created are pointing to the same spot in memory. They’re literally the exact same thing under different names. So when we invoke me , you , or someoneElse , it’s as if we’re invoking add .

Now, what if we take our add machine and pass it to another machine? Remember, it doesn’t matter who presses the () button, if it’s pressed, it’s going to run.

function add (x, y) {

return x + y

}

function addFive (x, addReference) {

return addReference(x, 5) // 15 - Press the button, run the machine.

}

addFive(10, add) // 15

Your brain might have got a little weird on this one, nothing new is going on here though. Instead of “pressing the button” on add , we pass add as an argument to addFive , rename it addReference , and then we “press the button” or invoke it.

This highlights some important concepts of the JavaScript language. First, just as you can pass a string or a number as an argument to a function, so too can you pass a reference to a function as an argument. When you do this the function you’re passing as an argument is called a callback function and the function you’re passing the callback function to is called a higher order function .

Because vocabulary is important, here’s the same code with the variables re-named to match the concepts they’re demonstrating.

function add (x,y) {

return x + y

}

function higherOrderFunction (x, callback) {

return callback(x, 5)

}

higherOrderFunction(10, add)

This pattern should look familiar, it’s everywhere. If you’ve ever used any of the JavaScript Array methods, you’ve used a callback. If you’ve ever used lodash, you’ve used a callback. If you’ve ever used jQuery, you’ve used a callback.

[1,2,3].map((i) => i + 5)

_.filter([1,2,3,4], (n) => n % 2 === 0 );

$('#btn').on('click', () =>

console.log('Callbacks are everywhere')

)

In general, there are two popular use cases for callbacks. The first, and what we see in the .map and _.filter examples, is a nice abstraction over transforming one value into another. We say “Hey, here’s an array and a function. Go ahead and get me a new value based on the function I gave you”. The second, and what we see in the jQuery example, is delaying execution of a function until a particular time. “Hey, here’s this function. Go ahead and invoke it whenever the element with an id of btn is clicked.” It’s this second use case that we’re going to focus on, “delaying execution of a function until a particular time”.

Right now we’ve only looked at examples that are synchronous. As we talked about at the beginning of this post, most of the apps we build don’t have all the data they need up front. Instead, they need to fetch external data as the user interacts with the app. We’ve just seen how callbacks can be a great use case for this because, again, they allow you to “delay execution of a function until a particular time”. It doesn’t take much imagination to see how we can adapt that sentence to work with data fetching. Instead of delaying execution of a function until a particular time , we can delay execution of a function until we have the data we need . Here’s probably the most popular example of this, jQuery’s getJSON method.

// updateUI and showError are irrelevant.

// Pretend they do what they sound like.

const id = 'tylermcginnis'

$.getJSON({

url: `https://api.github.com/users/${id}`,

success: updateUI,

error: showError,

})

We can’t update the UI of our app until we have the user’s data. So what do we do? We say, “Hey, here’s an object. If the request succeeds, go ahead and call success passing it the user’s data. If it doesn’t, go ahead and call error passing it the error object. You don’t need to worry about what each method does, just be sure to call them when you’re supposed to”. This is a perfect demonstration of using a callback for async requests.

At this point, we’ve learned about what callbacks are and how they can be beneficial both in synchronous and asynchronous code. What we haven’t talked yet is the dark side of callbacks. Take a look at this code below. Can you tell what’s happening?

// updateUI, showError, and getLocationURL are irrelevant.

// Pretend they do what they sound like.

const id = 'tylermcginnis'

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

$.getJSON({

url: `https://api.github.com/users/${id}`,

success: (user) => {

$.getJSON({

url: getLocationURL(user.location.split(',')),

success (weather) {

updateUI({

user,

weather: weather.query.results

})

},

error: showError,

})

},

error: showError

})

})

If it helps, you can play around with the live version here.

Notice we’ve added a few more layers of callbacks. First, we’re saying don’t run the initial AJAX request until the element with an id of btn is clicked. Once the button is clicked, we make the first request. If that request succeeds, we make a second request. If that request succeeds, we invoke the updateUI method passing it the data we got from both requests. Regardless of if you understood the code at first glance or not, objectively it’s much harder to read than the code before. This brings us to the topic of “Callback Hell”.

As humans, we naturally think sequentially. When you have nested callbacks inside of nested callbacks, it forces you out of your natural way of thinking. Bugs happen when there’s a disconnect between how your software is read and how you naturally think.

Like most solutions to software problems, a commonly prescribed approach for making “Callback Hell” easier to consume is to modularize your code.

function getUser(id, onSuccess, onFailure) {

$.getJSON({

url: `https://api.github.com/users/${id}`,

success: onSuccess,

error: onFailure

})

}

function getWeather(user, onSuccess, onFailure) {

$.getJSON({

url: getLocationURL(user.location.split(',')),

success: onSuccess,

error: onFailure,

})

}

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

getUser("tylermcginnis", (user) => {

getWeather(user, (weather) => {

updateUI({

user,

weather: weather.query.results

})

}, showError)

}, showError)

})

If it helps, you can play around with the live version here.

OK, the function names help us understand what’s going on, but is it objectively “better”? Not by much. We’ve put a band-aid over the readability issue of Callback Hell. The problem still exists that we naturally think sequentially and, even with the extra functions, nested callbacks break us out of that sequential way of thinking.

The next issue of callbacks has to do with inversion of control. When you write a callback, you’re assuming that the program you’re giving the callback to is responsible and will call it when (and only when) it’s supposed to. You’re essentially inverting the control of your program over to another program. When you’re dealing with libraries like jQuery, lodash, or even vanilla JavaScript, it’s safe to assume that the callback function will be invoked at the correct time with the correct arguments. However, for many third-party libraries, callback functions are the interface for how you interact with them. It’s entirely plausible that a third party library could, whether on purpose or accidentally, break how they interact with your callback.

function criticalFunction () {

// It's critical that this function

// gets called and with the correct

// arguments.

}

thirdPartyLib(criticalFunction)

Since you’re not the one calling criticalFunction , you have 0 control over when and with what argument it’s invoked. Most of the time this isn’t an issue, but when it is, it’s a big one.

Promises

Have you ever been to a busy restaurant without a reservation? When this happens, the restaurant needs a way to get back in contact with you when a table opens up. Historically, they’d just take your name and yell it when your table was ready. Then, as naturally occurs, they decided to start getting fancy. One solution was, instead of taking your name, they’d take your number and text you once a table opened up. This allowed you to be out of yelling range but more importantly, it allowed them to target your phone with ads whenever they wanted. Sound familiar? It should! OK, maybe it shouldn’t. It’s a metaphor for callbacks! Giving your number to a restaurant is just like giving a callback function to a third party service. You expect the restaurant to text you when a table opens up, just like you expect the third party service to invoke your function when and how they said they would. Once your number or callback function is in their hands though, you’ve lost all control.

Thankfully, there is another solution that exists. One that, by design, allows you to keep all the control. You’ve probably even experienced it before - it’s that little buzzer thing they give you. You know, this one.

If you’ve never used one before, the idea is simple. Instead of taking your name or number, they give you this device. When the device starts buzzing and glowing, your table is ready. You can still do whatever you’d like as you’re waiting for your table to open up, but now you don’t have to give up anything. In fact, it’s the exact opposite. They have to give you something. There is no inversion of control.

The buzzer will always be in one of three different states - pending , fulfilled , or rejected .

pending is the default, initial state. When they give you the buzzer, it’s in this state.

fulfilled is the state the buzzer is in when it’s flashing and your table is ready.

rejected is the state the buzzer is in when something goes wrong. Maybe the restaurant is about to close or they forgot someone rented out the restaurant for the night.

Again, the important thing to remember is that you, the receiver of the buzzer, have all the control. If the buzzer gets put into fulfilled , you can go to your table. If it gets put into fulfilled and you want to ignore it, cool, you can do that too. If it gets put into rejected , that sucks but you can go somewhere else to eat. If nothing ever happens and it stays in pending , you never get to eat but you’re not actually out anything.

Now that you’re a master of the restaurant buzzer thingy, let’s apply that knowledge to something that matters.

If giving the restaurant your number is like giving them a callback function, receiving the little buzzy thing is like receiving what’s called a “Promise”.

As always, let’s start with why . Why do Promises exist? They exist to make the complexity of making asynchronous requests more manageable. Exactly like the buzzer, a Promise can be in one of three states, pending , fulfilled or rejected . Unlike the buzzer, instead of these states representing the status of a table at a restaurant, they represent the status of an asynchronous request.

If the async request is still ongoing, the Promise will have a status of pending . If the async request was successfully completed, the Promise will change to a status of fulfilled . If the async request failed, the Promise will change to a status of rejected . The buzzer metaphor is pretty spot on, right?

Now that you understand why Promises exist and the different states they can be in, there are three more questions we need to answer.

- How do you create a Promise?

- How do you change the status of a promise?

- How do you listen for when the status of a promise changes?

1) How do you create a Promise?

This one is pretty straight forward. You create a new instance of Promise .

const promise = new Promise()

2) How do you change the status of a promise?

The Promise constructor function takes in a single argument, a (callback) function. This function is going to be passed two arguments, resolve and reject .

resolve - a function that allows you to change the status of the promise to fulfilled

reject - a function that allows you to change the status of the promise to rejected .

In the code below, we use setTimeout to wait 2 seconds and then invoke resolve . This will change the status of the promise to fulfilled .

const promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve() // Change status to 'fulfilled'

}, 2000)

})

We can see this change in action by logging the promise right after we create it and then again roughly 2 seconds later after resolve has been called.

Notice the promise goes from <pending> to <resolved> .

3) How do you listen for when the status of a promise changes?

In my opinion, this is the most important question. It’s cool we know how to create a promise and change its status, but that’s worthless if we don’t know how to do anything after the status changes.

One thing we haven’t talked about yet is what a promise actually is. When you create a new Promise , you’re really just creating a plain old JavaScript object. This object can invoke two methods, then , and catch . Here’s the key. When the status of the promise changes to fulfilled , the function that was passed to .then will get invoked. When the status of a promise changes to rejected , the function that was passed to .catch will be invoked. What this means is that once you create a promise, you’ll pass the function you want to run if the async request is successful to .then . You’ll pass the function you want to run if the async request fails to .catch .

Let’s take a look at an example. We’ll use setTimeout again to change the status of the promise to fulfilled after two seconds (2000 milliseconds).

function onSuccess () {

console.log('Success!')

}

function onError () {

console.log('💩')

}

const promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve()

}, 2000)

})

promise.then(onSuccess)

promise.catch(onError)

If you run the code above you’ll notice that roughly 2 seconds later, you’ll see “Success!” in the console. Again the reason this happens is because of two things. First, when we created the promise, we invoked resolve after ~2000 milliseconds - this changed the status of the promise to fulfilled . Second, we passed the onSuccess function to the promises’ .then method. By doing that we told the promise to invoke onSuccess when the status of the promise changed to fulfilled which it did after ~2000 milliseconds.

Now let’s pretend something bad happened and we wanted to change the status of the promise to rejected . Instead of calling resolve , we would call reject .

function onSuccess () {

console.log('Success!')

}

function onError () {

console.log('💩')

}

const promise = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

reject()

}, 2000)

})

promise.then(onSuccess)

promise.catch(onError)

Now this time instead of the onSuccess function being invoked, the onError function will be invoked since we called reject .

Now that you know your way around the Promise API, let’s start looking at some real code.

Remember the last async callback example we saw earlier?

function getUser(id, onSuccess, onFailure) {

$.getJSON({

url: `https://api.github.com/users/${id}`,

success: onSuccess,

error: onFailure

})

}

function getWeather(user, onSuccess, onFailure) {

$.getJSON({

url: getLocationURL(user.location.split(',')),

success: onSuccess,

error: onFailure,

})

}

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

getUser("tylermcginnis", (user) => {

getWeather(user, (weather) => {

updateUI({

user,

weather: weather.query.results

})

}, showError)

}, showError)

})

Is there any way we could use the Promise API here instead of using callbacks? What if we wrap our AJAX requests inside of a promise? Then we can simply resolve or reject depending on how the request goes. Let’s start with getUser .

function getUser(id) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

$.getJSON({

url: `https://api.github.com/users/${id}`,

success: resolve,

error: reject

})

})

}

Nice. Notice that the parameters of getUser have changed. Instead of receiving id , onSuccess , and onFailure , it just receives id . There’s no more need for those other two callback functions because we’re no longer inverting control. Instead, we use the Promise’s resolve and reject functions. resolve will be invoked if the request was successful, reject will be invoked if there was an error.

Next, let’s refactor getWeather . We’ll follow the same strategy here. Instead of taking in onSuccess and onFailure callback functions, we’ll use resolve and reject .

function getWeather(user) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

$.getJSON({

url: getLocationURL(user.location.split(',')),

success: resolve,

error: reject,

})

})

}

Looking good. Now the last thing we need to update is our click handler. Remember, here’s the flow we want to take.

- Get the user’s information from the Github API.

- Use the user’s location to get their weather from the Yahoo Weather API.

- Update the UI with the user’s info and their weather.

Let’s start with #1 - getting the user’s information from the Github API.

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

const userPromise = getUser('tylermcginnis')

userPromise.then((user) => {

})

userPromise.catch(showError)

})

Notice that now instead of getUser taking in two callback functions, it returns us a promise that we can call .then and .catch on. If .then is called, it’ll be called with the user’s information. If .catch is called, it’ll be called with the error.

Next, let’s do #2 - Use the user’s location to get their weather.

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

const userPromise = getUser('tylermcginnis')

userPromise.then((user) => {

const weatherPromise = getWeather(user)

weatherPromise.then((weather) => {

})

weatherPromise.catch(showError)

})

userPromise.catch(showError)

})

Notice we follow the exact same pattern we did in #1 but now we invoke getWeather passing it the user object we got from userPromise .

Finally, #3 - Update the UI with the user’s info and their weather.

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

const userPromise = getUser('tylermcginnis')

userPromise.then((user) => {

const weatherPromise = getWeather(user)

weatherPromise.then((weather) => {

updateUI({

user,

weather: weather.query.results

})

})

weatherPromise.catch(showError)

})

userPromise.catch(showError)

})

Here’s the full code you can play around with.

Our new code is better , but there are still some improvements we can make. Before we can make those improvements though, there are two more features of promises you need to be aware of, chaining and passing arguments from resolve to then .

Chaining

Both .then and .catch will return a new promise. That seems like a small detail but it’s important because it means that promises can be chained.

In the example below, we call getPromise which returns us a promise that will resolve in at least 2000 milliseconds. From there, because .then will return a promise, we can continue to chain our .then s together until we throw a new Error which is caught by the .catch method.

function getPromise () {

return new Promise((resolve) => {

setTimeout(resolve, 2000)

})

}

function logA () {

console.log('A')

}

function logB () {

console.log('B')

}

function logCAndThrow () {

console.log('C')

throw new Error()

}

function catchError () {

console.log('Error!')

}

getPromise()

.then(logA) // A

.then(logB) // B

.then(logCAndThrow) // C

.catch(catchError) // Error!

Cool, but why is this so important? Remember back in the callback section we talked about one of the downfalls of callbacks being that they force you out of your natural, sequential way of thinking. When you chain promises together, it doesn’t force you out of that natural way of thinking because chained promises are sequential. getPromise runs then logA runs then logB runs then... .

Just so you can see one more example, here’s a common use case when you use the fetch API. fetch will return you a promise that will resolve with the HTTP response. To get the actual JSON, you’ll need to call .json . Because of chaining, we can think about this in a sequential manner.

fetch('/api/user.json')

.then((response) => response.json())

.then((user) => {

// user is now ready to go.

})

Now that we know about chaining, let’s refactor our getUser / getWeather code from earlier to use it.

function getUser(id) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

$.getJSON({

url: `https://api.github.com/users/${id}`,

success: resolve,

error: reject

})

})

}

function getWeather(user) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

$.getJSON({

url: getLocationURL(user.location.split(',')),

success: resolve,

error: reject,

})

})

}

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

getUser("tylermcginnis")

.then(getWeather)

.then((weather) => {

// We need both the user and the weather here.

// Right now we just have the weather

updateUI() // ????

})

.catch(showError)

})

It looks much better, but now we’re running into an issue. Can you spot it? In the second .then we want to call updateUI . The problem is we need to pass updateUI both the user and the weather . Currently, how we have it set up, we’re only receiving the weather , not the user . Somehow we need to figure out a way to make it so the promise that getWeather returns is resolved with both the user and the weather .

Here’s the key. resolve is just a function. Any arguments you pass to it will be passed along to the function given to .then . What that means is that inside of getWeather , if we invoke resolve ourself, we can pass to it weather and user . Then, the second .then method in our chain will receive both user and weather as an argument.

function getWeather(user) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

$.getJSON({

url: getLocationURL(user.location.split(',')),

success(weather) {

resolve({ user, weather: weather.query.results })

},

error: reject,

})

})

}

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

getUser("tylermcginnis")

.then(getWeather)

.then((data) => {

// Now, data is an object with a

// "weather" property and a "user" property.

updateUI(data)

})

.catch(showError)

})

You can play around with the final code here

It’s in our click handler where you really see the power of promises shine compared to callbacks.

// Callbacks 🚫

getUser("tylermcginnis", (user) => {

getWeather(user, (weather) => {

updateUI({

user,

weather: weather.query.results

})

}, showError)

}, showError)

// Promises ✅

getUser("tylermcginnis")

.then(getWeather)

.then((data) => updateUI(data))

.catch(showError);

Following that logic feels natural because it’s how we’re used to thinking, sequentially. getUser then getWeather then update the UI with the data .

Now it’s clear that promises drastically increase the readability of our asynchronous code, but is there a way we can make it even better? Assume that you were on the TC39 committee and you had all the power to add new features to the JavaScript language. What steps, if any, would you take to improve this code?

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

getUser("tylermcginnis")

.then(getWeather)

.then((data) => updateUI(data))

.catch(showError)

})

As we’ve discussed, the code reads pretty nicely. Just as our brains work, it’s in a sequential order. One issue that we did run into was that we needed to thread the data ( users ) from the first async request all the way through to the last .then . This wasn’t a big deal, but it made us change up our getWeather function to also pass along users . What if we just wrote our asynchronous code the same way which we write our synchronous code? If we did, that problem would go away entirely and it would still read sequentially. Here’s an idea.

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

const user = getUser('tylermcginnis')

const weather = getWeather(user)

updateUI({

user,

weather,

})

})

Well, that would be nice. Our asynchronous code looks exactly like our synchronous code. There’s no extra steps our brain needs to take because we’re already very familiar with this way of thinking. Sadly, this obviously won’t work. As you know, if we were to run the code above, user and weather would both just be promises since that’s what getUser and getWeather return. But remember, we’re on TC39. We have all the power to add any feature to the language we want. As is, this code would be really tricky to make work. We’d have to somehow teach the JavaScript engine to know the difference between asynchronous function invocations and regular, synchronous function invocations on the fly. Let’s add a few keywords to our code to make it easier on the engine.

First, let’s add a keyword to the main function itself. This could clue the engine to the fact that inside of this function, we’re going to have some asynchronous function invocations. Let’s use async for this.

$("#btn").on("click", async () => {

const user = getUser('tylermcginnis')

const weather = getWeather(user)

updateUI({

user,

weather,

})

})

Cool. That seems reasonable. Next let’s add another keyword to let the engine know exactly when a function being invoked is asynchronous and is going to return a promise. Let’s use await . As in, “Hey engine. This function is asynchronous and returns a promise. Instead of continuing on like you typically do, go ahead and ‘await’ the eventual value of the promise and return it before continuing”. With both of our new async and await keywords in play, our new code will look like this.

$("#btn").on("click", async () => {

const user = await getUser('tylermcginnis')

const weather = await getWeather(user.location)

updateUI({

user,

weather,

})

})

Pretty slick. We’ve invented a reasonable way to have our asynchronous code look and behave as if it were synchronous. Now the next step is to actually convince someone on TC39 that this is a good idea. Lucky for us, as you probably guessed by now, we don’t need to do any convincing because this feature is already part of JavaScript and it’s called Async/Await .

Don’t believe me? Here’s our live code now that we’ve added Async/Await to it. Feel free to play around with it.

async functions return a promise

Now that you’ve seen the benefit of Async/Await, let’s discuss some smaller details that are important to know. First, anytime you add async to a function, that function is going to implicitly return a promise.

async function getPromise(){}

const promise = getPromise()

Even though getPromise is literally empty, it’ll still return a promise since it was an async function.

If the async function returns a value, that value will also get wrapped in a promise. That means you’ll have to use .then to access it.

async function add (x, y) {

return x + y

}

add(2,3).then((result) => {

console.log(result) // 5

})

await without async is bad

If you try to use the await keyword inside of a function that isn’t async , you’ll get an error.

$("#btn").on("click", () => {

const user = await getUser('tylermcginnis') // SyntaxError: await is a reserved word

const weather = await getWeather(user.location) // SyntaxError: await is a reserved word

updateUI({

user,

weather,

})

})

Here’s how I think about it. When you add async to a function it does two things. It makes it so the function itself returns (or wraps what gets returned in) a promise and makes it so you can use await inside of it.

Error Handling

You may have noticed we cheated a little bit. In our original code we had a way to catch any errors using .catch . When we switched to Async/Await, we removed that code. With Async/Await, the most common approach is to wrap your code in a try/catch block to be able to catch the error.

$("#btn").on("click", async () => {

try {

const user = await getUser('tylermcginnis')

const weather = await getWeather(user.location)

updateUI({

user,

weather,

})

} catch (e) {

showError(e)

}

})

Guide to JavaScript’s prototype (and ES6 Classes)

This is originally part of our Advanced JavaScript course. However, it’s applicable to us here as well.

You can’t get very far in JavaScript without dealing with objects. They’re foundational to almost every aspect of the JavaScript programming language. In fact, learning how to create objects is probably one of the first things you studied when you were starting out. With that said, in order to most effectively learn about prototypes in JavaScript, we’re going to channel our inner Jr. developer and go back to the basics.

Objects are key/value pairs. The most common way to create an object is with curly braces {} and you add properties and methods to an object using dot notation.

let animal = {}

animal.name = 'Leo'

animal.energy = 10

animal.eat = function (amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

animal.sleep = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

animal.play = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

Simple. Now odds are in our application we’ll need to create more than one animal. Naturally, the next step for this would be to encapsulate that logic inside of a function that we can invoke whenever we needed to create a new animal. We’ll call this pattern Functional Instantiation and we’ll call the function itself a “constructor function” since it’s responsible for “constructing” a new object.

Functional Instantiation

function Animal (name, energy) {

let animal = {}

animal.name = name

animal.energy = energy

animal.eat = function (amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

animal.sleep = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

animal.play = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

return animal

}

const leo = Animal('Leo', 7)

const snoop = Animal('Snoop', 10)

"I thought this was an Advanced JavaScript course...?" - Your brain It is. We’ll get there.

Now whenever we want to create a new animal (or more broadly speaking a new “instance”), all we have to do is invoke our Animal function, passing it the animal’s name and energy level. This works great and it’s incredibly simple. However, can you spot any weaknesses with this pattern? The biggest and the one we’ll attempt to solve has to do with the three methods - eat , sleep , and play . Each of those methods are not only dynamic, but they’re also completely generic. What that means is that there’s no reason to re-create those methods as we’re currently doing whenever we create a new animal. We’re just wasting memory and making each animal object bigger than it needs to be. Can you think of a solution? What if instead of re-creating those methods every time we create a new animal, we move them to their own object then we can have each animal reference that object? We can call this pattern Functional Instantiation with Shared Methods , wordy but descriptive.

Functional Instantiation with Shared Methods

const animalMethods = {

eat(amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

},

sleep(length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

},

play(length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

}

function Animal (name, energy) {

let animal = {}

animal.name = name

animal.energy = energy

animal.eat = animalMethods.eat

animal.sleep = animalMethods.sleep

animal.play = animalMethods.play

return animal

}

const leo = Animal('Leo', 7)

const snoop = Animal('Snoop', 10)

By moving the shared methods to their own object and referencing that object inside of our Animal function, we’ve now solved the problem of memory waste and overly large animal objects.

Object.create

Let’s improve our example once again by using Object.create . Simply put, Object.create allows you to create an object which will delegate to another object on failed lookups . Put differently, Object.create allows you to create an object and whenever there’s a failed property lookup on that object, it can consult another object to see if that other object has the property. That was a lot of words. Let’s see some code.

const parent = {

name: 'Stacey',

age: 35,

heritage: 'Irish'

}

const child = Object.create(parent)

child.name = 'Ryan'

child.age = 7

console.log(child.name) // Ryan

console.log(child.age) // 7

console.log(child.heritage) // Irish

So in the example above, because child was created with Object.create(parent) , whenever there’s a failed property lookup on child , JavaScript will delegate that look up to the parent object. What that means is that even though child doesn’t have a heritage property, parent does so when you log child.heritage you’ll get the parent 's heritage which was Irish .

Now with Object.create in our tool shed, how can we use it in order to simplify our Animal code from earlier? Well, instead of adding all the shared methods to the animal one by one like we’re doing now, we can use Object.create to delegate to the animalMethods object instead. To sound really smart, let’s call this one Functional Instantiation with Shared Methods and Object.create

Functional Instantiation with Shared Methods and Object.create

const animalMethods = {

eat(amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

},

sleep(length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

},

play(length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

}

function Animal (name, energy) {

let animal = Object.create(animalMethods)

animal.name = name

animal.energy = energy

return animal

}

const leo = Animal('Leo', 7)

const snoop = Animal('Snoop', 10)

leo.eat(10)

snoop.play(5)

So now when we call

So now when we call leo.eat , JavaScript will look for the eat method on the leo object. That lookup will fail, then, because of Object.create, it’ll delegate to the animalMethods object which is where it’ll find eat .

So far, so good. There are still some improvements we can make though. It seems just a tad “hacky” to have to manage a separate object ( animalMethods ) in order to share methods across instances. That seems like a common feature that you’d want to be implemented into the language itself. Turns out it is and it’s the whole reason you’re here - prototype .

So what exactly is prototype in JavaScript? Well, simply put, every function in JavaScript has a prototype property that references an object. Anticlimactic, right? Test it out for yourself.

function doThing () {}

console.log(doThing.prototype) // {}

What if instead of creating a separate object to manage our methods (like we’re doing with animalMethods ), we just put each of those methods on the Animal function’s prototype? Then all we would have to do is instead of using Object.create to delegate to animalMethods , we could use it to delegate to Animal.prototype . We’ll call this pattern Prototypal Instantiation .

Prototypal Instantiation

function Animal (name, energy) {

let animal = Object.create(Animal.prototype)

animal.name = name

animal.energy = energy

return animal

}

Animal.prototype.eat = function (amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

Animal.prototype.sleep = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

Animal.prototype.play = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

const leo = Animal('Leo', 7)

const snoop = Animal('Snoop', 10)

leo.eat(10)

snoop.play(5)

Hopefully, you just had a big “aha” moment. Again,

Hopefully, you just had a big “aha” moment. Again, prototype is just a property that every function in JavaScript has and, as we saw above, it allows us to share methods across all instances of a function. All our functionality is still the same but now instead of having to manage a separate object for all the methods, we can just use another object that comes built into the Animal function itself, Animal.prototype .

Let’s. Go. Deeper.

At this point we know three things:

- How to create a constructor function.

- How to add methods to the constructor function’s prototype.

- How to use Object.create to delegate failed lookups to the function’s prototype.

Those three tasks seem pretty foundational to any programming language. Is JavaScript really that bad that there’s no easier, “built-in” way to accomplish the same thing? As you can probably guess at this point there is, and it’s by using the new keyword.

What’s nice about the slow, methodical approach we took to get here is you’ll now have a deep understanding of exactly what the new keyword in JavaScript is doing under the hood.

Looking back at our Animal constructor, the two most important parts were creating the object and returning it. Without creating the object with Object.create , we wouldn’t be able to delegate to the function’s prototype on failed lookups. Without the return statement, we wouldn’t ever get back the created object.

function Animal (name, energy) {

let animal = Object.create(Animal.prototype)

animal.name = name

animal.energy = energy

return animal

}

Here’s the cool thing about new - when you invoke a function using the new keyword, those two lines are done for you implicitly (“under the hood”) and the object that is created is called this .

Using comments to show what happens under the hood and assuming the Animal constructor is called with the new keyword, it can be re-written as this.

function Animal (name, energy) {

// const this = Object.create(Animal.prototype)

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

// return this

}

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

const snoop = new Animal('Snoop', 10)

and without the “under the hood” comments

function Animal (name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

Animal.prototype.eat = function (amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

Animal.prototype.sleep = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

Animal.prototype.play = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

const snoop = new Animal('Snoop', 10)

Again the reason this works and that the this object is created for us is because we called the constructor function with the new keyword. If you leave off new when you invoke the function, that this object never gets created nor does it get implicitly returned. We can see the issue with this in the example below.

function Animal (name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

const leo = Animal('Leo', 7)

console.log(leo) // undefined

The name for this pattern is Pseudoclassical Instantiation .

If JavaScript isn’t your first programming language, you might be getting a little restless.

“WTF this dude just re-created a crappier version of a Class” - You

For those unfamiliar, a Class allows you to create a blueprint for an object. Then whenever you create an instance of that Class, you get an object with the properties and methods defined in the blueprint.

Sound familiar? That’s basically what we did with our Animal constructor function above. However, instead of using the class keyword, we just used a regular old JavaScript function to re-create the same functionality. Granted, it took a little extra work as well as some knowledge about what happens “under the hood” of JavaScript but the results are the same.

Here’s the good news. JavaScript isn’t a dead language. It’s constantly being improved and added to by the TC-39 committee. What that means is that even though the initial version of JavaScript didn’t support classes, there’s no reason they can’t be added to the official specification. In fact, that’s exactly what the TC-39 committee did. In 2015, EcmaScript (the official JavaScript specification) 6 was released with support for Classes and the class keyword. Let’s see how our Animal constructor function above would look like with the new class syntax.

class Animal {

constructor(name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

eat(amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

sleep(length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

play(length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

}

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

const snoop = new Animal('Snoop', 10)

Pretty clean, right?

So if this is the new way to create classes, why did we spend so much time going over the old way? The reason for that is because the new way (with the class keyword) is primarily just “syntactical sugar” over the existing way we’ve called the pseudo-classical pattern. In order to fully understand the convenience syntax of ES6 classes, you first must understand the pseudo-classical pattern.

At this point we’ve covered the fundamentals of JavaScript’s prototype. The rest of this post will be dedicated to understanding other “good to know” topics related to it. In another post, we’ll look at how we can take these fundamentals and use them to understand how inheritance works in JavaScript.

Array Methods

We talked in depth above about how if you want to share methods across instances of a class, you should stick those methods on the class’ (or function’s) prototype. We can see this same pattern demonstrated if we look at the Array class. Historically you’ve probably created your arrays like this

const friends = []

Turns out that’s just sugar over creating a new instance of the Array class.

const friendsWithSugar = []

const friendsWithoutSugar = new Array()

One thing you might have never thought about is how does every instance of an array have all of those built-in methods ( splice , slice , pop , etc)?

Well as you now know, it’s because those methods live on Array.prototype and when you create a new instance of Array , you use the new keyword which sets up that delegation to Array.prototype on failed lookups.

We can see all the array’s methods by simply logging Array.prototype .

console.log(Array.prototype)

/*

concat: ƒn concat()

constructor: ƒn Array()

copyWithin: ƒn copyWithin()

entries: ƒn entries()

every: ƒn every()

fill: ƒn fill()

filter: ƒn filter()

find: ƒn find()

findIndex: ƒn findIndex()

forEach: ƒn forEach()

includes: ƒn includes()

indexOf: ƒn indexOf()

join: ƒn join()

keys: ƒn keys()

lastIndexOf: ƒn lastIndexOf()

length: 0n

map: ƒn map()

pop: ƒn pop()

push: ƒn push()

reduce: ƒn reduce()

reduceRight: ƒn reduceRight()

reverse: ƒn reverse()

shift: ƒn shift()

slice: ƒn slice()

some: ƒn some()

sort: ƒn sort()

splice: ƒn splice()

toLocaleString: ƒn toLocaleString()

toString: ƒn toString()

unshift: ƒn unshift()

values: ƒn values()

*/

The exact same logic exists for Objects as well. All objects will delegate to Object.prototype on failed lookups which is why all objects have methods like toString and hasOwnProperty .

Static Methods

Up until this point we’ve covered the why and how of sharing methods between instances of a Class. However, what if we had a method that was important to the Class, but didn’t need to be shared across instances? For example, what if we had a function that took in an array of Animal instances and determined which one needed to be fed next? We’ll call it nextToEat .

function nextToEat (animals) {

const sortedByLeastEnergy = animals.sort((a,b) => {

return a.energy - b.energy

})

return sortedByLeastEnergy[0].name

}

It doesn’t make sense to have nextToEat live on Animal.prototype since we don’t want to share it amongst all instances. Instead, we can think of it as more of a helper method. So if nextToEat shouldn’t live on Animal.prototype , where should we put it? Well, the obvious answer is we could just stick nextToEat in the same scope as our Animal class then reference it when we need it as we normally would.

class Animal {

constructor(name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

eat(amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

sleep(length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

play(length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

}

function nextToEat (animals) {

const sortedByLeastEnergy = animals.sort((a,b) => {

return a.energy - b.energy

})

return sortedByLeastEnergy[0].name

}

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

const snoop = new Animal('Snoop', 10)

console.log(nextToEat([leo, snoop])) // Leo

Now this works, but there’s a better way.

Whenever you have a method that is specific to a class itself but doesn’t need to be shared across instances of that class, you can add it as a

staticproperty of the class.

class Animal {

constructor(name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

eat(amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

sleep(length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

play(length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

static nextToEat(animals) {

const sortedByLeastEnergy = animals.sort((a,b) => {

return a.energy - b.energy

})

return sortedByLeastEnergy[0].name

}

}

Now, because we added nextToEat as a static property on the class, it lives on the Animal class itself (not its prototype) and can be accessed using Animal.nextToEat .

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

const snoop = new Animal('Snoop', 10)

console.log(Animal.nextToEat([leo, snoop])) // Leo

Because we’ve followed a similar pattern throughout this post, let’s take a look at how we would accomplish this same thing using ES5. In the example above we saw how using the static keyword would put the method directly onto the class itself. With ES5, this same pattern is as simple as just manually adding the method to the function object.

function Animal (name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

Animal.prototype.eat = function (amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

Animal.prototype.sleep = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

Animal.prototype.play = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

Animal.nextToEat = function (animals) {

const sortedByLeastEnergy = animals.sort((a,b) => {

return a.energy - b.energy

})

return sortedByLeastEnergy[0].name

}

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

const snoop = new Animal('Snoop', 10)

console.log(Animal.nextToEat([leo, snoop])) // Leo

Getting the prototype of an object

Regardless of whichever pattern you used to create an object, getting that object’s prototype can be accomplished using the Object.getPrototypeOf method.

function Animal (name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

Animal.prototype.eat = function (amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

Animal.prototype.sleep = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

Animal.prototype.play = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

const prototype = Object.getPrototypeOf(leo)

console.log(prototype)

// {constructor: ƒ, eat: ƒ, sleep: ƒ, play: ƒ}

prototype === Animal.prototype // true

There are two important takeaways from the code above.

First, you’ll notice that proto is an object with 4 methods, constructor , eat , sleep , and play . That makes sense. We used getPrototypeOf passing in the instance, leo getting back that instances’ prototype, which is where all of our methods are living. This tells us one more thing about prototype as well that we haven’t talked about yet. By default, the prototype object will have a constructor property which points to the original function or the class that the instance was created from. What this also means is that because JavaScript puts a constructor property on the prototype by default, any instances will be able to access their constructor via instance.constructor .

The second important takeaway from above is that Object.getPrototypeOf(leo) === Animal.prototype . That makes sense as well. The Animal constructor function has a prototype property where we can share methods across all instances and getPrototypeOf allows us to see the prototype of the instance itself.

function Animal (name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

console.log(leo.constructor) // Logs the constructor function

To tie in what we talked about earlier with Object.create , the reason this works is because any instances of Animal are going to delegate to Animal.prototype on failed lookups. So when you try to access leo.constructor , leo doesn’t have a constructor property so it will delegate that lookup to Animal.prototype which indeed does have a constructor property. If this paragraph didn’t make sense, go back and read about Object.create above.

You may have seen proto used before to get an instances’ prototype. That’s a relic of the past. Instead, use Object.getPrototypeOf(instance) as we saw above.

Determining if a property lives on the prototype

There are certain cases where you need to know if a property lives on the instance itself or if it lives on the prototype the object delegates to. We can see this in action by looping over our leo object we’ve been creating. Let’s say the goal was the loop over leo and log all of its keys and values. Using a for in loop, that would probably look like this.

function Animal (name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

Animal.prototype.eat = function (amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

Animal.prototype.sleep = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

Animal.prototype.play = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

for(let key in leo) {

console.log(`Key: ${key}. Value: ${leo[key]}`)

}

What would you expect to see? Most likely, it was something like this -

Key: name. Value: Leo

Key: energy. Value: 7

However, what you saw if you ran the code was this -

Key: name. Value: Leo

Key: energy. Value: 7

Key: eat. Value: function (amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

Key: sleep. Value: function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

Key: play. Value: function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

Why is that? Well, a for in loop is going to loop over all of the enumerable properties on both the object itself as well as the prototype it delegates to. Because by default any property you add to the function’s prototype is enumerable, we see not only name and energy , but we also see all the methods on the prototype - eat , sleep , and play . To fix this, we either need to specify that all of the prototype methods are non-enumerable or we need a way to only console.log if the property is on the leo object itself and not the prototype that leo delegates to on failed lookups. This is where hasOwnProperty can help us out.

hasOwnProperty is a property on every object that returns a boolean indicating whether the object has the specified property as its own property rather than on the prototype the object delegates to. That’s exactly what we need. Now with this new knowledge, we can modify our code to take advantage of hasOwnProperty inside of our for in loop.

...

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

for(let key in leo) {

if (leo.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

console.log(`Key: ${key}. Value: ${leo[key]}`)

}

}

And now what we see are only the properties that are on the leo object itself rather than on the prototype leo delegates to as well.

Key: name. Value: Leo

Key: energy. Value: 7

If you’re still a tad confused about hasOwnProperty , here is some code that may clear it up.

function Animal (name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

Animal.prototype.eat = function (amount) {

console.log(`${this.name} is eating.`)

this.energy += amount

}

Animal.prototype.sleep = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is sleeping.`)

this.energy += length

}

Animal.prototype.play = function (length) {

console.log(`${this.name} is playing.`)

this.energy -= length

}

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

leo.hasOwnProperty('name') // true

leo.hasOwnProperty('energy') // true

leo.hasOwnProperty('eat') // false

leo.hasOwnProperty('sleep') // false

leo.hasOwnProperty('play') // false

Check if an object is an instance of a Class

Sometimes you want to know whether an object is an instance of a specific class. To do this, you can use the instanceof operator. The use case is pretty straight forward but the actual syntax is a bit weird if you’ve never seen it before. It works like this

object instanceof Class

The statement above will return true if object is an instance of Class and false if it isn’t. Going back to our Animal example we’d have something like this.

function Animal (name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

function User () {}

const leo = new Animal('Leo', 7)

leo instanceof Animal // true

leo instanceof User // false

The way that instanceof works is it checks for the presence of constructor.prototype in the object’s prototype chain. In the example above, leo instanceof Animal is true because Object.getPrototypeOf(leo) === Animal.prototype . In addition, leo instanceof User is false because Object.getPrototypeOf(leo) !== User.prototype .

Creating new agnostic constructor functions

Can you spot the error in the code below?

function Animal (name, energy) {

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

const leo = Animal('Leo', 7)

Even seasoned JavaScript developers will sometimes get tripped up on the example above. Because we’re using the pseudoclassical pattern that we learned about earlier, when the Animal constructor function is invoked, we need to make sure we invoke it with the new keyword. If we don’t, then the this keyword won’t be created and it also won’t be implicitly returned.

As a refresher, the commented out lines are what happens behind the scenes when you use the new keyword on a function.

function Animal (name, energy) {

// const this = Object.create(Animal.prototype)

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

// return this

}

This seems like too important of a detail to leave up to other developers to remember. Assuming we’re working on a team with other developers, is there a way we could ensure that our Animal constructor is always invoked with the new keyword? Turns out there is and it’s by using the instanceof operator we learned about previously.

If the constructor was called with the new keyword, then this inside of the body of the constructor will be an instanceof the constructor function itself. That was a lot of big words. Here’s some code.

function Animal (name, energy) {

if (this instanceof Animal === false) {

console.warn('Forgot to call Animal with the new keyword')

}

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

Now instead of just logging a warning to the consumer of the function, what if we re-invoke the function but with the new keyword this time?

function Animal (name, energy) {

if (this instanceof Animal === false) {

return new Animal(name, energy)

}

this.name = name

this.energy = energy

}

Now regardless of if Animal is invoked with the new keyword, it’ll still work properly.

Re-creating Object.create

Throughout this post, we’ve relied heavily upon Object.create in order to create objects which delegate to the constructor function’s prototype. At this point, you should know how to use Object.create inside of your code but one thing that you might not have thought of is how Object.create actually works under the hood. In order for you to really understand how Object.create works, we’re going to re-create it ourselves. First, what do we know about how Object.create works?

- It takes in an argument that is an object.

- It creates an object that delegates to the argument object on failed lookups.

- It returns the new created object.

Let’s start off with #1.

Object.create = function (objToDelegateTo) {

}

Simple enough.

Now #2 - we need to create an object that will delegate to the argument object on failed lookups. This one is a little more tricky. To do this, we’ll use our knowledge of how the new keyword and prototypes work in JavaScript. First, inside the body of our Object.create implementation, we’ll create an empty function. Then, we’ll set the prototype of that empty function equal to the argument object. Then, in order to create a new object, we’ll invoke our empty function using the new keyword. If we return that newly created object, that’ll finish #3 as well.

Object.create = function (objToDelegateTo) {

function Fn(){}

Fn.prototype = objToDelegateTo

return new Fn()

}

Wild. Let’s walk through it.

When we create a new function, Fn in the code above, it comes with a prototype property. When we invoke it with the new keyword, we know what we’ll get back is an object that will delegate to the function’s prototype on failed lookups. If we override the function’s prototype, then we can decide which object to delegate to on failed lookups. So in our example above, we override Fn 's prototype with the object that was passed in when Object.create was invoked which we call objToDelegateTo .

Note that we’re only supporting a single argument to Object.create. The official implementation also supports a second, optional argument which allows you to add more properties to the created object.

Arrow Functions

Arrow functions don’t have their own this keyword. As a result, arrow functions can’t be constructor functions and if you try to invoke an arrow function with the new keyword, it’ll throw an error.

const Animal = () => {}

const leo = new Animal() // Error: Animal is not a constructor

Also, because we demonstrated above that the pseudo-classical pattern can’t be used with arrow functions, arrow functions also don’t have a prototype property.

const Animal = () => {}

console.log(Animal.prototype) // undefined

From IIFEs to CommonJS to ES6 Modules

This is originally part of our Advanced JavaScript course. However, it’s applicable to us here as well.

I’ve taught JavaScript for a long time to a lot of people. Consistently the most commonly under-learned aspect of the language is the module system. There’s a good reason for that. Modules in JavaScript have a strange and erratic history. In this post, we’ll walk through that history and you’ll learn modules of the past to better understand how JavaScript modules work today.

Before we learn how to create modules in JavaScript, we first need to understand what they are and why they exist. Look around you right now. Any marginally complex item that you can see is probably built using individual pieces that when put together, form the item.

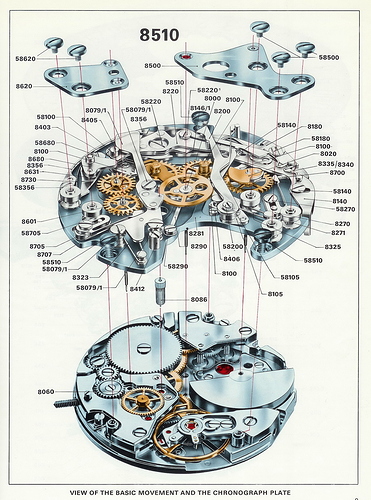

Let’s take a watch for example.

A simple wristwatch is made up of hundreds of internal pieces. Each has a specific purpose and clear boundaries for how it interacts with the other pieces. Put together, all of these pieces form the whole of the watch. Now I’m no watch engineer, but I think the benefits of this approach are pretty transparent.

Reusability

Take a look at the diagram above one more time. Notice how many of the same pieces are being used throughout the watch. Through highly intelligent design decisions centered on modularity, they’re able to re-use the same components throughout different aspects of the watch design. This ability to re-use pieces simplifies the manufacturing process and, I’m assuming, increases profit.

Composability

The diagram is a beautiful illustration of composability. By establishing clear boundaries for each individual component, they’re able to compose each piece together to create a fully functioning watch out of tiny, focused pieces.

Leverage

Think about the manufacturing process. This company isn’t making watches, it’s making individual components that together form a watch. They could create those pieces in house, they could outsource them and leverage other manufacturing plants, it doesn’t matter. The most important thing is that each piece comes together in the end to form a watch - where those pieces were created is irrelevant.

Isolation

Understanding the whole system is difficult. Because the watch is composed of small, focused pieces, each of those pieces can be thought about, built and or repaired in isolation. This isolation allows multiple people to work individually on the watch while not bottle-necking each other. Also if one of the pieces breaks, instead of replacing the whole watch, you just have to replace the individual piece that broke.

Organization

Organization is a byproduct of each individual piece having a clear boundary for how it interacts with other pieces. With this modularity, organization naturally occurs without much thought.

We’ve seen the obvious benefits of modularity when it comes to everyday items like a watch, but what about software? Turns out, it’s the same idea with the same benefits. Just how the watch was designed, we should design our software separated into different pieces where each piece has a specific purpose and clear boundaries for how it interacts with other pieces. In software, these pieces are called modules . At this point, a module might not sound too different from something like a function or a React component. So what exactly would a module encompass?

Each module has three parts - dependencies (also called imports), code, and exports.

imports

code

exports

Dependencies (Imports)

When one module needs another module, it can import that module as a dependency. For example, whenever you want to create a React component, you need to import the react module. If you want to use a library like lodash , you’d need import the lodash module.

Code

After you’ve established what dependencies your module needs, the next part is the actual code of the module.

Exports

Exports are the “interface” to the module. Whatever you export from a module will be available to whoever imports that module.

Enough with the high-level stuff, let’s dive into some real examples.

First, let’s look at React Router. Conveniently, they have a modules folder. This folder is filled with… modules, naturally. So in React Router, what makes a “module”. Turns out, for the most part, they map their React components directly to modules. That makes sense and in general, is how you separate components in a React project. This works because if you re-read the watch above but swap out “module” with “component”, the metaphors still make sense.

Let’s look at the code from the MemoryRouter module. Don’t worry about the actual code for now, but focus on more of the structure of the module.

// imports

import React from "react";

import { createMemoryHistory } from "history";

import Router from "./Router";

// code

class MemoryRouter extends React.Component {

history = createMemoryHistory(this.props);

render() {

return (

<Router

history={this.history}

children={this.props.children}

/>;

)

}

}

// exports

export default MemoryRouter;

You’ll notice at the top of the module they define their imports, or what other modules they need to make the MemoryRouter module work properly. Next, they have their code. In this case, they create a new React component called MemoryRouter . Then at the very bottom, they define their export, MemoryRouter . This means that whenever someone imports the MemoryRouter module, they’ll get the MemoryRouter component.

Now that we understand what a module is, let’s look back at the benefits of the watch design and see how, by following a similar modular architecture, those same benefits can apply to software design.

Reusability

Modules maximize reusability since a module can be imported and used in any other module that needs it. Beyond this, if a module would be beneficial in another program, you can create a package out of it. A package can contain one or more modules and can be uploaded to NPM to be downloaded by anyone. react , lodash , and jquery are all examples of NPM packages since they can be installed from the NPM directory.

Composability

Because modules explicitly define their imports and exports, they can be easily composed. More than that, a sign of good software is that is can be easily deleted. Modules increase the “delete-ability” of your code.

Leverage

The NPM registry hosts the world’s largest collection of free, reusable modules (over 700,000 to be exact). Odds are if you need a specific package, NPM has it.

Isolation

The text we used to describe the isolation of the watch fits perfectly here as well. “Understanding the whole system is difficult. Because (your software) is composed of small, focused (modules), each of those (modules) can be thought about, built and or repaired in isolation. This isolation allows multiple people to work individually on the (app) while not bottle-necking each other. Also if one of the (modules) breaks, instead of replacing the whole (app), you just have to replace the individual (module) that broke.”

Organization

Perhaps the biggest benefit in regards to modular software is organization. Modules provide a natural separation point. Along with that, as we’ll see soon, modules prevent you from polluting the global namespace and allow you to avoid naming collisions.

At this point, you know the benefits and understand the structure of modules. Now it’s time to actually start building them. Our approach to this will be pretty methodical. The reason for that is because, as mentioned earlier, modules in JavaScript have a strange history. Even though there are “newer” ways to create modules in JavaScript, some of the older flavors still exist and you’ll see them from time to time. If we jump straight to modules in 2018, I’d be doing you a disservice. With that said, we’re going to take it back to late 2010. AngularJS was just released and jQuery is all the rage. Companies are finally using JavaScript to build complex web applications and with that complexity comes a need to manage it - via modules.

Your first intuition for creating modules may be to separate code by files.

// users.js

var users = ["Tyler", "Sarah", "Dan"]

function getUsers() {

return users

}

// dom.js

function addUserToDOM(name) {

const node = document.createElement("li")

const text = document.createTextNode(name)

node.appendChild(text)

document.getElementById("users")

.appendChild(node)

}

document.getElementById("submit")

.addEventListener("click", function() {

var input = document.getElementById("input")

addUserToDOM(input.value)

input.value = ""

})

var users = window.getUsers()

for (var i = 0; i < users.length; i++) {

addUserToDOM(users[i])

}

<!-- index.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Users</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Users</h1>

<ul id="users"></ul>

<input

id="input"

type="text"

placeholder="New User">

</input>

<button id="submit">Submit</button>

<script src="users.js"></script>

<script src="dom.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

The full code can be found here .

OK. We’ve successfully separated our app into its own files. Does that mean we’ve successfully implemented modules? No. Absolutely not. Literally, all we’ve done is separate where the code lives. The only way to create a new scope in JavaScript is with a function. All the variables we declared that aren’t in a function are just living on the global object. You can see this by logging the window object in the console. You’ll notice we can access, and worse, change addUsers , users , getUsers , addUserToDOM . That’s essentially our entire app. We’ve done nothing to separate our code into modules, all we’ve done is separate it by physical location. If you’re new to JavaScript, this may be a surprise to you but it was probably your first intuition for how to implement modules in JavaScript.

So if file separation doesn’t give us modules, what does? Remember the advantages to modules - reusability, composability, leverage, isolation, organization. Is there a native feature of JavaScript we could use to create our own “modules” that would give us the same benefits? What about a regular old function? When you think of the benefits of a function, they align nicely to the benefits of modules. So how would this work? What if instead of having our entire app live in the global namespace, we instead expose a single object, we’ll call it APP . We can then put all the methods our app needs to run under the APP , which will prevent us from polluting the global namespace. We could then wrap everything else in a function to keep it enclosed from the rest of the app.

// App.js

var APP = {}

// users.js

function usersWrapper () {

var users = ["Tyler", "Sarah", "Dan"]

function getUsers() {

return users

}

APP.getUsers = getUsers

}

usersWrapper()

// dom.js

function domWrapper() {

function addUserToDOM(name) {

const node = document.createElement("li")

const text = document.createTextNode(name)

node.appendChild(text)

document.getElementById("users")

.appendChild(node)

}

document.getElementById("submit")

.addEventListener("click", function() {

var input = document.getElementById("input")

addUserToDOM(input.value)

input.value = ""

})

var users = APP.getUsers()

for (var i = 0; i < users.length; i++) {

addUserToDOM(users[i])

}

}

domWrapper()

<!-- index.html -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Users</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Users</h1>

<ul id="users"></ul>

<input

id="input"

type="text"

placeholder="New User">

</input>

<button id="submit">Submit</button>

<script src="app.js"></script> <script src="users.js"></script>

<script src="dom.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

The full code can be found here .

Now if you look at the window object, instead of it having all the important pieces of our app, it just has APP and our wrapper functions, usersWrapper and domWrapper . More important, none of our important code (like users ) can be modified since they’re no longer on the global namespace.

Let’s see if we can take this a step further. Is there a way to get rid of our wrapper functions? Notice that we’re defining and then immediately invoking them. The only reason we gave them a name was so we could immediately invoke them. Is there a way to immediately invoke an anonymous function so we wouldn’t have to give them a name? Turns out there is and it even has a fancy name - Immediately Invoked Function Expression or IIFE for short.

IIFE

Here’s what it looks like.

(function () {

console.log('Pronounced IF-EE')

})()

Notice it’s just an anonymous function expression that we’ve wrapped in parens ().

(function () {

console.log('Pronounced IF-EE')

})

Then, just like any other function, in order to invoke it, we add another pair of parens to the end of it.

(function () {

console.log('Pronounced IF-EE')

})()

Now let’s use our knowledge of IIFEs to get rid of our ugly wrapper functions and clean up the global namespace even more.

// users.js

(function () {

var users = ["Tyler", "Sarah", "Dan"]

function getUsers() {

return users

}

APP.getUsers = getUsers

})()

// dom.js

(function () {

function addUserToDOM(name) {

const node = document.createElement("li")

const text = document.createTextNode(name)

node.appendChild(text)

document.getElementById("users")

.appendChild(node)

}

document.getElementById("submit")

.addEventListener("click", function() {

var input = document.getElementById("input")

addUserToDOM(input.value)

input.value = ""

})

var users = APP.getUsers()

for (var i = 0; i < users.length; i++) {

addUserToDOM(users[i])

}

})()

The full code can be found here .